For Abuild Version 1.1.6, June 30, 2011

Copyright © 2007-2011 Jay Berkenbilt, Argon ST

Table of Contents

- Notes For Users of Abuild Version 1.0

- How to Read This Manual

- Acknowledgments

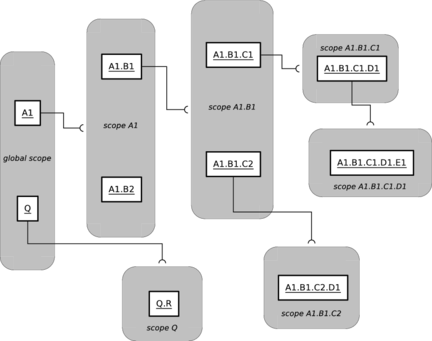

- Notes About Documentation Formatting

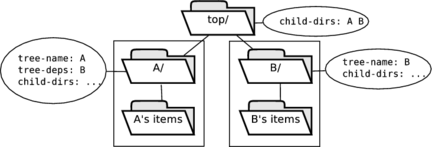

- I. Quick Start

- II. Normal Operation

- 4. Build Items and Build Trees

- 5. Target Types, Platform Types, and Platforms

- 6. Build Item Dependencies

- 7. Multiple Build Trees

- 8. Help System

- 9. Telling Abuild What to Build

- 10. Integration with Automated Test Frameworks

- 11. Backing Areas

- 12. Explicit Read-Only and Read/Write Paths

- 13. Command-Line Reference

- 14. Survey of Additional Capabilities

- III. Advanced Functionality

- 15. The

Abuild.confFile - 16. The

Abuild.backingFile - 17. The Abuild Interface System

- 18. The GNU Make backend

- 19. The Groovy Backend

- 19.1. A Crash Course in Groovy

- 19.2. The

Abuild.groovyFile - 19.3. Directory Structure for Java Builds

- 19.4. Class Paths and Class Path Variables

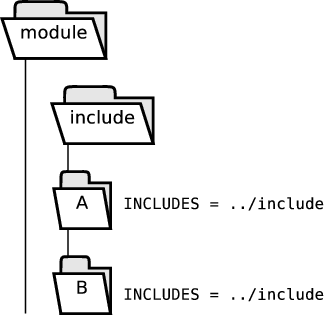

- 19.5. Basic Java Rules Functionality

- 19.6. Advanced Customization of Java Rules

- 19.7. The Abuild Groovy Environment

- 19.8. Using QTest With the Groovy Backend

- 19.9. Groovy Rules

- 19.10. Additional Information for Rule Authors

- 20. Controlling and Processing Abuild's Output

- 21. Shared Libraries

- 22. Build Item Rules and Automatically Generated Code

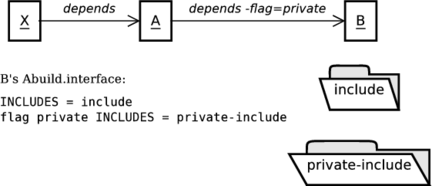

- 23. Interface Flags

- 24. Cross-Platform Support

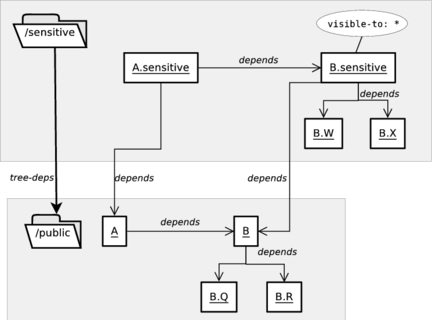

- 25. Build Item Visibility

- 26. Linking With Whole Libraries

- 27. Opaque Wrappers

- 28. Optional Dependencies

- 29. Enhancing Abuild with Plugins

- 30. Best Practices

- 31. Monitored Mode

- 32. Sample XSL-T Scripts

- 33. Abuild Internals

- 33.1. Avoiding Recursive Make

- 33.2. Starting Abuild in an Output Directory

- 33.3. Traversal Details

- 33.4. Compatibility Framework

- 33.5. Construction of the Build Set

- 33.6. Construction of the Build Graph

- 33.7. Implementation of the Abuild Interface System

- 33.8. Loading Abuild Interfaces

- 33.9. Parameter Block Implementation

- 15. The

- IV. Appendices

- A. Release Notes

- B. Major Changes from Version 1.0 to Version 1.1

- C. Upgrading from 1.0 to Version 1.1

- D. Known Limitations

- E. Online Help Files

- E.1. abuild --help groovy

- E.2. abuild --help helpfiles

- E.3. abuild --help make

- E.4. abuild --help usage

- E.5. abuild --help vars

- E.6. abuild --help rules rule:empty

- E.7. abuild --help rules rule:groovy

- E.8. abuild --help rules rule:java

- E.9. abuild --help rules rule:autoconf

- E.10. abuild --help rules rule:ccxx

- E.11. abuild --help rules toolchain:gcc

- E.12. abuild --help rules toolchain:mingw

- E.13. abuild --help rules toolchain:msvc

- E.14. abuild --help rules toolchain:unix_compiler

- F.

--dump-dataFormat - G.

--dump-interfacesFormat - H.

--dump-build-graphFormat - I. The

ccxx.mkFile - J. The

java.groovyandgroovy.groovyFiles - K. The Deprecated XML-based Ant Backend

- L. List of Examples

- Index

List of Figures

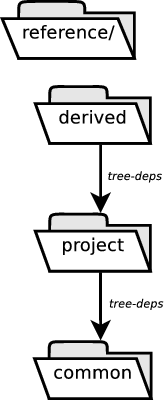

- 6.1. Build Item Scopes

- 7.1. Top-Level

Abuild.conf - 7.2. Build Trees in

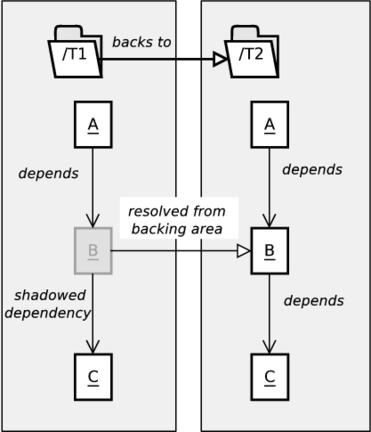

general/reference - 11.1. Shadowed Dependency

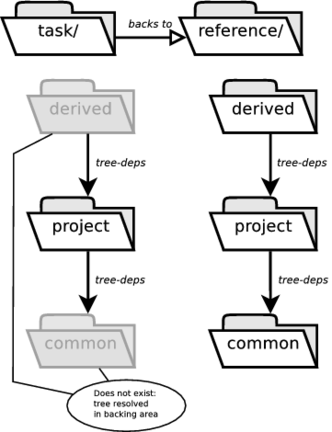

- 11.2. Build Trees in

general/task - 11.3. Build Trees in

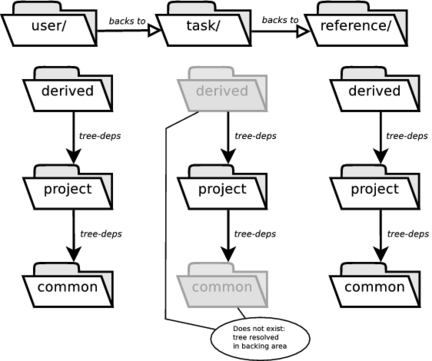

general/user - 23.1. Private Interface Flag

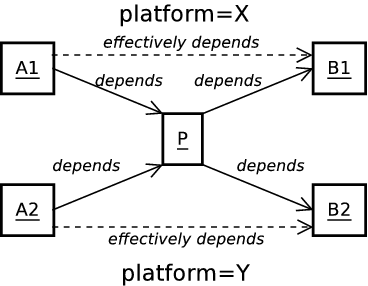

- 24.1. Multiplatform Pass-through Build Item

- 25.1. Build Item Visibility

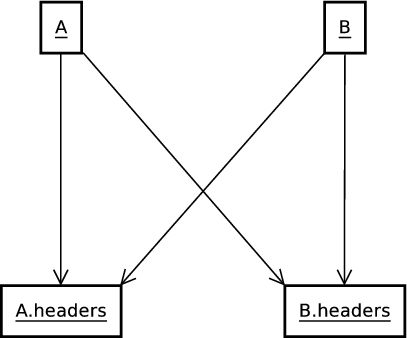

- 30.1. Hidden Circular Dependency

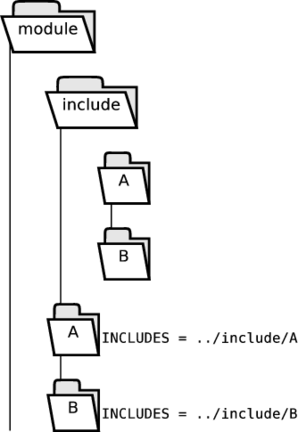

- 30.2. Shared Include Directory

- 30.3. Separate Include Directories

List of Tables

This manual is written for abuild version 1.1. If you are a user of abuild version 1.0 and are just looking for a summary of what changed, please see Appendix B, Major Changes from Version 1.0 to Version 1.1. The material there includes a summary of a change along with cross references to relevant sections of documentation.

Please note that, with a small handful of exceptions, abuild version 1.1 is be able to build software that used abuild 1.0 with few if any modifications. The section on changes in version 1.1 (Appendix B, Major Changes from Version 1.0 to Version 1.1) includes a detailed list of things to watch out for during upgrading and when running in 1.0-compatibility mode.

Welcome to the abuild manual! You may always find the latest copy of this manual on abuild's website. This manual is designed to get you up and running with abuild quickly: the most essential and common topics are presented first so that you can just start at the beginning and stop reading when you feel that you've seen enough to get going. Then, when you are ready, you can come back for documentation on the full depth of abuild's functionality. If you come across something in the first reading that you don't understand, it's probably safe to skip it and come back when you're more comfortable. As each new concept is presented, it is enhanced with examples. A list of all the examples in the document can be found in Appendix L, List of Examples. If you are just looking for changes from previous versions of abuild, please see Appendix A, Release Notes and Appendix B, Major Changes from Version 1.0 to Version 1.1.

This manual is divided into four parts. Each part of the document draws on material introduced in the earlier parts. Although earlier parts of the documentation are intended to be understandable without the material from the later parts, they contain forward cross references where appropriate.

In Part I, “Quick Start”, we cover basic information that should help you come up to speed on using abuild for day-to-day work. It is geared toward people who are working on an existing software baseline that uses abuild. In Part I, you will learn about what abuild is and the types of problems it was designed to solve, be introduced to some basic terminology, and see a few examples of how to perform some simple build operations. This part of the manual is very short and is designed to be readable in one sitting. Casual users of abuild may have no need to read past Part I.

In Part II, “Normal Operation”, we introduce the most common features of abuild. All the basic features are covered, and a few advanced features are covered. All the information you need for simple projects has been presented by the end of Part II.

In Part III, “Advanced Functionality”, we introduce advanced topics. By the end of Part III, you will have been exposed to every feature of abuild.

Part IV, “Appendices” consists of a small handful of appendices.

For those wishing to go still deeper, the abuild source code is heavily commented, and the software comes with a thorough automated test suite that covers every feature of the software and many error conditions as well.

The creation of abuild would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support of my employer, Argon ST. Argon not only recognized the important role of a strong build tool in contributing to the overall quality and reliability of its software, but saw the value of releasing it to the open source community in hopes of making an even broader contribution.

There are many people within Argon who helped take abuild to where it is now, but among these, a handful of people deserve special mention:

Brian Reid, who first introduced me to Groovy, the language that is at the heart of abuild version 1.1's significantly improved Java support, and who kept the momentum going for making abuild's Groovy-based Java framework a reality

Brian Reid, Joe Schettino, Kathleen Friesen, and Brandon Barlow who met with me many times to help hammer out and test early versions of the Groovy-based Java framework

Brandon Barlow for tirelessly testing numerous builds with abuild 1.1 during its alpha period.

Cass Dalton, who has frequently served as a sounding board as I think about new abuild capabilities, and who has played a significant role in helping to ensure that abuild is as stable and widely usable as possible

Chris Costa, who served as a sounding board and contributed numerous ideas throughout the entire development process of abuild, including conducting a thorough review of the abuild 1.0 documentation

Andrew Hayden, who spent many hours reviewing and critiquing the entire manual prior to the release of version 1.0 and who contributed many feature ideas designed to ease implementation of an abuild Eclipse plugin

Joe Davidson, the first abuild evangelist who has been invaluable in getting abuild to become as widely accepted within Argon ST as it is

Gavin Mulligan, who has consistently taken the time to report any problem, no matter how small, and who probably reported more issues than everyone else combined during abuild's pre-1.0 alpha period

Bob Tamaru, who in addition to being a mentor and supporter for most of my career, provided considerable assistance to me as I presented the case to Argon ST to allow me to release abuild as an open source project

This manual is written in docbook. The PDF version of the manual was generated with Apache fop, which as of this writing, is still incomplete. There are a few known issues with the PDF version of the documentation. Hopefully these issues will all be addressed as fop matures.

There are many bad line breaks. Sometimes words are incorrectly hyphenated, and line breaks also occur between two dashes in command line options and even between the two

+characters of “C++”.In many of the example listings, there are lines that would be longer than the shaded boxes in the PDF output. We wrap those lines and place a backslash (

\) character just before and after the extra line breaks. This is done for both the HTML and the PDF output even though the long lines are only a problem for the PDF output.Some paragraphs appear to have extra indentation. This is because the formatting software generates a hard space whenever we have an index term marker in the text.

There are no bookmarks. It would be good if we could create bookmarks to the chapter headings, but as of this writing, the documented procedure for doing this does not appear to work.

The material contained in this part is geared toward new and casual users of abuild. Without going into excessive detail, this part gives you a quick tour of abuild's functionality and presents a few examples of routine build operations. By the end of this part, you should be able to use abuild for simple build operations, and you should have begun to get a feel for the basic configuration files.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Abuild is a system designed to build large software projects or related families of software projects that are divided into a potentially large number of components. It is specifically designed for software projects that are continually evolving and that may span multiple languages and platforms. The basic idea behind abuild is simple: when building a single component (module, unit, etc.) of a software package, the developer should be able to focus on that component exclusively. Abuild requires each component developer to declare, by name, the list of other components on which his or her component depends. It is then abuild's responsibility to provide whatever is needed to the build environment to make other required items visible.

You might want to think of abuild as an object-oriented build system. When working with abuild, the fundamental unit is the build item. A build item is essentially a single collection of code, usually contained within one directory, that is built as a unit. A build item may produce one or more products (libraries, executables, JAR files, etc.) that other build items may want to use. It is the responsibility of each build item to provide information about its products that may be used by other items that depend on it. This information is provided by a build item in its abuild interface. In this way, knowledge about how to use a build item is encapsulated within that build item rather than being spread around throughout the other components of a system.

To implement this core functionality, abuild provides its own system for managing build items as well as the dependencies and relationships among them. It also provides various build rules implemented with underlying tools, specifically GNU Make and Apache Ant accessed using the Groovy programming language, to perform the actual build steps. We refer to these underlying tools as backends. Although the bulk of the functionality and sophistication of abuild comes from its own core capabilities rather than the build rules, the rules have rich functionality as well. Abuild is intended to be your build system. It is not intended, as some other tools are, to wrap around your existing build system. [1]

Support for compilation in multiple programming languages and on

multiple platforms, including embedded platforms, is central to

abuild's design. Abuild is designed to allow build items to

be built on multiple platforms simultaneously. An important way

in which abuild achieves this functionality is to do all of its

work inside of an output directory. When

abuild performs the actual build, it always creates an output

directory named

abuild-.

When abuild invokes make, it does so

in that directory. By actually invoking the backend in the

output directory, abuild avoids the situation of temporary

files conflicting with each other on multiple simultaneous builds

of a given build item on multiple platforms. For ant-based

builds (using either the supported Groovy backend or the

deprecated xml-based ant backend), each build is given a private

ant platformProject object whose

basedir is set to the output directory.

Abuild is designed to never create or remove any output files

outside of its output directories. This enables abuild's

cleanup operation to simply remove all output directories created

by any instance of abuild, and also reduces the likelihood of

unintentionally mixing generated products with version-controlled

sources.

The following list shows the font conventions used throughout this document for the names of different kinds of items.

literal text |

replaceable text |

build items and build item

scope names

|

| Abuild.conf keys, flags, and traits |

Abuild.interface variables, java

properties, and make variables

|

Abuild.interface keywords

|

| commands and build targets |

command line options and build

sets

|

environment variables

|

file names and make/Groovy rule

sets

|

| platforms, platform types, and target types |

This section describes what you can expect in terms of abuild version numbers and non-compatible changes.

Each abuild release is assigned a version number. For abuild releases, we use the following version numbering convention:

major.minor.prerelease-or-update

The major field of the version number

indicates the major version number. It changes whenever a major

release is made. A new major release of abuild represents a

wholesale change in the way abuild works. Major release are

expected to be very infrequent.

The minor field of the version number

indicates the minor version number. It changes whenever a minor

release is made. A minor release is an incremental release that

may introduce significant new features, fix bugs, or change the

way some things work, but it will not fundamentally shift the

way abuild works. We impose tight restrictions on the

introduction of non-backward-compatible changes in minor

releases as discussed below.

The prerelease-or-update field can

indicate either a prerelease version or an update release of a

specific minor version. A prerelease is an alpha or beta

release or a release candidate that precedes a regular release.

An update release may contain bug fixes or new features as long

as no non-compatible changes are made to existing functionality.

Allowing new non-breaking features to be introduced in an update

release makes it possible to add features to abuild

incrementally while still guaranteeing as much compatibility as

possible. There is no support for a prerelease of an update to

a specific minor version (like 1.1.1.b1).

Before a regular major or minor release, there may be a series

of alpha releases, beta releases, and release candidates. In

those cases, the prerelease-or-update

field of the version number is either

“a”,

“b”, or

“rc” followed by a number. The

prerelease version numbers clearly indicate which regular

release the prerelease applies to. For example, version

1.3.a4 would be the fourth alpha release

preceding the release of version 1.3.0.

After any major or minor release, it is possible that a small

problem may be corrected in a bug-fix release. In such a

release, the prerelease-or-update

field contains a number that indicates which bug-fix release

this is. For example, version 1.2.1 would be

a bug-fix release to version 1.2.0.

Historical note: the first release of abuild 1.0 was just version 1.0, not version 1.0.0. The use of “x.y.0” was introduced with version 1.1.0 so that “abuild x.y” could unambiguously refer to all update releases of minor version x.y rather than just the first.

In a new major release of abuild (e.g., version 2.0.0), there is no promise that changes will be backward compatible, nor is there any expectation that configuration files from older abuild releases will work with the new version. When possible, care will be taken to mitigate any inconvenience such as providing upgrade scripts.

In each new minor release of abuild, there may be new features

and backward-compatible changes. In minor releases, we adopt a

stricter policy regarding non-backward-compatible changes.

Specifically, non-backward-compatible changes may be introduced

only if the changed construct generated a deprecation warning in

the previous minor release. In other words, if particular

construct in version 1.3 is going to be

dropped or changed in a non-compatible way, the change can't be

made until version 1.5. In version

1.4, the new way may work, but use of the

deprecated construct must still work and must generate a

warning. The old way can be dropped entirely in version

1.5 once users have had a chance to adjust

their configuration files. In that way, users who take every

minor release upgrade can be guaranteed that they will not

experience surprise non-compatible changes, and they will not

have to update their configuration files at the same time that

they upgrade abuild.

With alpha releases, there is no commitment to avoiding non-compatible changes. In particular, a feature that was introduced into abuild during an alpha testing period may be modified in non-compatible ways or dropped entirely during the course of alpha testing. During beta testing, every effort will be made to avoid non-compatible changes, but they are still allowed. No non-compatible changes will be made from the first release candidate through the next minor release.

Specific exceptions may be made to any of the above rules, but any such exceptions will be clearly stated in the release notes or the documentation. It may happen, for example, that a particular new feature is still in development when a release is made. In that case, the release notes may declare that feature to still be alpha, in which case non-compatible changes can be introduced in the next release.

We'll clarify with some concrete examples. Suppose a new

feature is planned for version 1.4 of

abuild. It would be okay if the first implementation of that

feature appeared in version 1.4.a2 and if the

feature were changed in a non-compatible way in

1.4.a6. However, after version

1.4.0 was released, the next non-compatible

change would not be permitted until version

1.5.a1, and even then, the feature as it

worked in version 1.4.0 would still have to

work, though a deprecation warning would be issued. The old

version 1.4.x way of doing things could stop

working altogether in version 1.6.a1. It is

also okay to add a new feature within a

minor release. For example, it's okay if

1.0.3 adds some feature that wasn't there in

1.0.2 as long as everything that worked in

1.0.2 works the same way in

1.0.3. In other words, although everything

that worked in 1.0.2 must work in

1.0.3 , there's no expectation that

everything that works in 1.0.3 must have

worked in 1.0.2.

This section describes many of the principles upon which abuild was designed. Understanding this material is not critical to being able to use abuild just to do simple compiles, but knowing these things will help you use abuild better and will provide a context for understanding what it does.

- Build Integrity

Abuild puts the integrity of the build over all other concerns. Abuild includes several rigorously enforced integrity checks throughout its implementation in order to prevent many of the most common causes of build integrity problems.

- Strict Dependency Management

Build items must explicitly declare dependencies on other build items. These dependencies are declared by name, not by path. The same mechanism within abuild that is used to declare a dependency is also used to provide visibility to the dependent build item. (A build item reads the interfaces of only those build items on which it directly or indirectly depends.) In this way, it is impossible to accidentally become dependent on something by unwittingly using files that it provides. Abuild guarantees that there are no circular dependencies among build items and also provides a fundamental guarantee that all build items in a dependency chain resolve names to paths in a consistent way within the dependency tree.

- Directory Structure Neutrality

Build items refer to each other only by name and never by path. Abuild resolves build item names to paths internally and provides path information at runtime as needed. This makes any specific abuild installation agnostic about directory structure and makes it possible to move things around without changing any build rules. In this way, abuild stays out of the way when it's time to reorganize your project.

- Focus on One Item at a Time

When using abuild, you are generally able to focus on building just the item you are working on without having to worry about the details of the items it depends on. Abuild does all the work of figuring out what your environment has to look like to give you access to your dependencies. It can then start a local build from anywhere and pass the right information to that local build. This is achieved through encapsulation of knowledge about a build item's products inside the build item itself and making that knowledge available to its users through an abuild-specific interface.

- Environment Independence

Abuild does not require you to have any project-specific or source tree-specific environment variables set, be using any particular shell or operating system, or have the abuild software itself installed in any particular location. Abuild is designed so that having the abuild command in your path is sufficient for doing a build. This keeps abuild independent from any specific source tree or project. Abuild can be used to build a single-source-file, stand-alone program or an elaborate product line consisting of hundreds or thousands of components. It can be also used for multiple projects on the same system at the same time. No special path settings or environment variable settings are required to use abuild, other than ensuring that the external tools that your build requires (GNU Make, compilers, etc.) are available and in your path.

- Support for Parallel and Distributed Builds

When building multiple items, abuild creates a build set consisting of all the items to be built. It computes the directories in which it needs to build and invokes the build iteratively in those directories. Abuild automatically figures out what can be built in parallel and what the build order should be by inspecting the dependency graph. Abuild avoids many of the pitfalls that get in the way of parallel and distributed operation including recursive execution, shell-based loops for iteration, file system-based traversal, and writing files to the source directory.

- Support for Multiple Platforms

Abuild was designed to work on multiple platforms. It includes a structure for referring to platforms and for encapsulating platform-specific knowledge. This makes it easier to create portable build structures for portable code.

- Efficiency

Abuild aims to be as efficient as possible without compromising build integrity. Abuild calculates as much as possible up front when it is first invoked, and it passes that information to backend build programs through automatically-generated files created inside its own output directories. By computing the information one time, abuild significantly reduces the degree to which its backend build programs' rules have to use external helper applications to compute information they need. Abuild's configuration files and build tree traversal steps are designed in such a way that abuild never has to perform unbounded searches of a build tree. This enables startup to be fast even on build trees containing thousands of build items.

- Encapsulation

Build items encapsulate knowledge about what is required by their users in order to make use of them at build time. The user may also create build items with restricted scope, thus allowing private things to be kept private. This makes it possible to refactor or reorganize individual components of a system without affecting the build files of other build items that depend on them.

- Declarative Build Files

The majority of build item configuration files are declarative: they contain descriptions of what needs to be done, rather than information about how to do it. Most end user configuration files contain nothing but variable settings or key/value pairs and are independent of the platform or compiler used to build the item. For those cases in which a declarative system is insufficient to express what needs to do be done, abuild provides several mechanisms for specific steps to be defined and made available to the items that need them.

- Support for Multiple Backends

The parts of abuild that manage dependencies and build integrity are distinct from the parts of abuild that actually perform builds. Abuild current uses either GNU Make or Apache Ant, accessed through a Groovy language front end, to perform builds. [2] The internal integration between abuild and its backend build programs is fairly loose, and adding additional backends requires relatively minor and localized code changes. In addition, abuild requires only the backends that a particular build tree uses to be present on your system when you are performing a build. That is, if you are building only Java code, you don't need GNU Make, and if you're building only C and C++ code, you don't need a Java or ant environment.

[1] Abuild can, however, interoperate with other build systems as needed, which may be useful while transitioning a software development effort to using abuild.

[2] There is also support for ant using xml files. This was the primary mechanism for using ant in abuild 1.0, but it is deprecated in version 1.1 in favor of the much more flexible and capable Groovy-based backend. Throughout this document, we refer to it as the “deprecated xml-based ant” framework.

Table of Contents

You may always find the latest version of abuild by following the links on abuild's website. To use abuild, the following items must be available on your system:

GNU Make version 3.81 or higher is required if you are building any build items that use GNU Make as a backend. This would include platform-independent code and C/C++ code, but not Java code.

A Java 5 or newer Java SDK is required if you are going to use abuild to build Java code. Abuild is known to work with OpenJDK 1.6.

Apache Ant version 1.7.0 or newer is required if you are building any Java code. If you are using abuild's deprecated xml-based ant framework, then you also need ant-contrib version 1.0.b3 or later installed in either ant's or abuild's lib directory.

Perl version 5.8 or newer is required if you are performing any GNU Make-based builds.

Perl version 5.8 or newer and qtest version 1.0 or newer are required if you are using the qtest automated test framework. Abuild's own test suite uses qtest. Note also that qtest requires GNU diffutils. Any version should do.

In order to use abuild's autoconf support, you need autoconf version 2.59 or newer, automake version 1.9 or newer. These are also required for abuild's test suite to pass since the test suite exercises its autoconf support.

If you are planning on building any GNU Make-based build items on Windows, Cygwin is required. For a Java-only abuild installation on Windows, Cygwin and Perl are not required. It is hoped that a future version of abuild will not require Cygwin. For details on using Cygwin with abuild, please see Section 2.4, “Additional Requirements for Windows Environments”.

To build abuild, you must also have version 1.35 or newer of boost. Abuild uses several boost libraries, including regex, thread, system, filesystem, and date_time as well as several header-only libraries such as asio, bind, and function. Abuild is known to buildable by gcc and Microsoft Visual C++ (7.1 or newer), but it should be buildable by any compiler that supports boost 1.35. In order for shared library support to work properly with gcc, gcc must be configured to use the GNU linker. [3] Abuild itself contains C++ code and Java code, so all the runtime requirements for both systems are required to build abuild.

In order to build abuild's Java code, which is required if you are doing any Java-based builds, you must have at least version 1.5.7 of Groovy. It is recommended that you have at least version 1.6.0. It is not required that you have Groovy to run abuild because abuild includes an embedded version of the Groovy environment, but a full installation of Groovy is required in order to do the initial bootstrapping build of abuild's Java code. [4]

As of abuild version 1.1.0, abuild is known to work with Groovy versions 1.6.7 and 1.7-RC-1, which were the latest available versions at the time of the release. Upgrading abuild's embedded version of Groovy is as simple as just replacing the embeddable Groovy JAR file inside of abuild's lib directory. Just delete the old one and copy the new one in. abuild will automatically find it even though its name will have changed to include the later version number. Ideally, you should also rebuild abuild's java support from source and rerun abuild's test suite just to be sure abuild still works properly with the latest Groovy.

Since abuild determines where it is being run from when it is

invoked, a binary distribution of abuild is not tied to a

particular installation path. It finds the root of its

installation directory by walking up the path from the abuild

executable until it finds a directory that contains

make/abuild.mk. This makes it easy to have

multiple versions of abuild installed simultaneously, and it

also makes it easy to create relocatable binary distributions of

abuild.

Abuild itself does not require any environment variables to be

set, but ant and/or the Java

development environment may. If you have the

JAVA_HOME and ANT_HOME environment

variables set, abuild will honor them when selecting which copy

of java to run and where to find the ant JAR files. Otherwise,

it will run java and

ant from your path to make those

determinations. Although abuild is explicitly tested to work

without either ANT_HOME or

JAVA_HOME set, if any Java builds are being done,

abuild will start up a little more quickly if they are set. As

many other applications expect these to be set, it is recommended

that you set JAVA_HOME and

ANT_HOME. When abuild invokes Java for any of

the Java-based backends, it will automatically add all the JAR

files in $ANT_HOME/lib to the classpath as

well as all JAR files in abuild's own lib

directory. Abuild includes a copy of Groovy's embeddable JAR

in its own lib directory. You can copy

additional JAR files into lib as well, but

if you do so, just remember that those JAR files will not

automatically be available to users whose abuild installations

do not include them.

As you begin using abuild, you may find yourself generating a

collection of useful utility build items for things like specific

third-party libraries, external compilers, documentation

generators, or test frameworks. There is a small collection of

contributed build items in the

abuild-contrib package, which is available

at abuild's web

site. These may have additional requirements. For

details, please see the information about

abuild-contrib on the website.

Abuild is self-hosting: it can be built with itself, or for

bootstrapping, it can be built with a GNU Makefile that uses

abuild's internal GNU Make support.

To build abuild's Java code, you also need

Groovy, Apache

Ant and a Java development environment. Please see

the file src/README.build in the source

distribution for instructions on building abuild.

If you are creating a binary distribution or installing from

source, please see the file src/README.build

in the source directory. If you are installing from a pre-built

binary distribution, simply extract the binary distribution in

any directory. Abuild imposes no requirements on where the

directory should be or what it should be called as long as its

contents remain in the correct relative locations. You may make

a symbolic link to the actual bin/abuild

executable from a directory in your path. Abuild will follow

this link when attempting to discover the path of its

installation directory. You may also add the abuild

distribution's bin directory to your path,

or invoke abuild by the full path to its executable.

[5]

To build abuild and use it in a Windows environment for make-based builds, certain pieces of the Cygwin environment are required. [6] Note that abuild is able to build with and be built by Visual C++ on Windows. It uses Cygwin only for its development tools. Cygwin is not required to run executables built by abuild in a Windows environment, including abuild itself. However, Cygwin is required to supply make and perl to abuild. The following parts of Cygwin are required:

- Devel

autoconf automake make - System

rebase - Util

diffutils

Perl is required, but appears to be installed by default in recent Cygwin installations.

Note that rebaseall (from the rebase package) may need to be run

in order for fork to work from perl with

certain modules. (Although abuild itself doesn't call

fork from perl,

qtest, which is used for abuild's

test suite, does.)

Other modules may also be desirable. In particular,

libxml2 from the Text

section is required in order to run certain parts of abuild's

test suite, though the test suite will just issue a warning and

skip those tests without failing if it can't find

xmllint.

If you intend to use autoconf from Windows and you have Rational

Rose installed, you may need to create

/usr/bin/hostinfo (inside of the Cygwin

environment) as

#!/bin/false

so that ./configure's running of hostinfo doesn't run hostinfo from Rational Rose.

In order to use Visual C++ with abuild, you must have your environment set up to invoke Visual C++ command line tools. This can be achieved by running the shortcut supplied with Visual Studio, or you can create a batch file on your own. The following batch file would enable you to run abuild from a Cygwin environment with the environment set up for running Visual C++ from Visual Studio 7.1 (.NET 2003):

@echo off call "%VS71COMNTOOLS%"\vsvars32.bat C:\cygwin\cygwin.bat

Adjust as needed if your Cygwin is installed other than in

C:\cygwin or you have a different version of

Visual C++ installed.

In order to use qtest with abuild under Windows, the Cygwin version of Perl must be the first perl in your path.

Abuild creates output directories in the source directory, and

all generated files are created inside of these

abuild-generated directories. All output directories are named

abuild-*. It is recommended that you

configure hooks or triggers in your version control system to

prevent these directories or their contents from being

accidentally checked in. It may also be useful to prevent

Abuild.backing from being checked in since

this file always contains information about the local

configuration rather than something that would be CM controlled.

If it is your policy to allow these to be checked in, they should

be prevented from appearing in shared areas such as the trunk.

[7]

[3] The only reason for the GNU linker requirement is that abuild currently knows about -fPIC. It would be better to have a more robust way of configuring flags for position-independent-code, but it's not clear how to do this without replicating all the knowledge built into libtool or having some autoconf-like method of configuring abuild at runtime.

[4] Besides, every Java programmer should have a copy of Groovy installed!

[5]

If abuild is not invoked as an absolute path, it will iterate

through the directories in your PATH trying to

find itself. Therefore, abuild may fail to work properly if

you invoke it programmatically, pass

\“abuild” to it as

argv[0], and do not have the copy of

abuild you are invoking in your path before any other copy of

abuild. This limitation should never impact users who are

invoking abuild normally from the command line or through a

shell or other program that searches the path.

[6] This may cease to be true in a future version of abuild.

[7]

Note, however, that the abuild test suite contains

Abuild.backing files, so any CM system

that contains abuild must have an exception for abuild

itself. It's conceivable that other tools could also have

reasons to have checked in Abuild.backing

files in test suites or as templates.

Table of Contents

In this chapter, we will describe the basics of running abuild

on a few simple build items, and we will describe how those build

items are constructed. We will gloss over many details that will

be covered later in the documentation. The goal of this chapter

is to give you enough information to work on simple build items

that belong to existing build trees. Definitions of

build item and build

tree appear below. More detailed information on them

can be found in Chapter 4, Build Items and Build Trees. The

examples we refer to in this chapter can be found in

doc/example/basic in your abuild source or

binary distribution.

Abuild imposes few system-based restrictions on how you set it up and use it, but here are a few important things to keep in mind:

Avoid putting spaces in path names wherever possible. Although abuild tries to behave properly with respect to spaces in path names and is known to handle many cases correctly, make is notoriously bad at it. If you try to use spaces in path names, it is very likely that you will eventually run into problems as they generally cause trouble in a command-line environment.

Be careful about the lengths of path names. Although abuild itself imposes no limits on this, you may run up against operating system limits if your paths are too long. In particular, Windows has a maximum path name length of 260 characters. If you have a build tree whose root already has a long path and you then have Java classes that are buried deep within a package-based directory structure, you can bump into the 260-character limit faster than you'd think. On Windows, it is recommended that you keep your build tree roots as close to the root of the drive as possible. On any modern UNIX system, you should not run into any path name length issues.

Here are a few basic terms you'll need to get started:

- build item

A build item is the most basic item that is built by abuild. It usually consists of a directory that contains files that are built. Any directory that contains an

Abuild.conffile is a build item. We refer to the build item whoseAbuild.confresides in the current directory as the current build item.- build tree

A build tree is a collection of build items arranged hierarchically in the file system. All build items in a build tree may refer to each other by name. Each build item knows the locations of its children within the file system hierarchy and the names of the build items on which it depends.

- build forest

A build forest is a collection of build trees. If there are multiple build trees in a forest, there may be one-way visibility relationships among the trees, which are declared similarly to dependency relationships among build items. We will return to this concept later in the documentation.

- target

A target is some specific product to be built. The term “target” means exactly the same thing with abuild as it does with other build systems such as make or ant. In fact, with the exception of a small handful of “special” targets, abuild simply passes any targets given to it onto the backend build system for processing. The most common targets are all and clean. For a more complete discussion of targets, see Section 9.1, “Build Targets”. Be careful not to confuse target with target type, defined in Section 5.1, “Platform Structure”.

For a more complete description of build items, build trees, and build forests, please see Chapter 4, Build Items and Build Trees.

Full details on compiler support and compiler selection are

covered in Section 24.1, “Platform Selection”. To get

started, on Linux systems, abuild will build with

gcc by default. On Windows, if you

run abuild from a shell that is appropriately set up to run

Microsoft Visual C++ (as by following the command prompt shortcut

provided as part of your Visual C++ implementation), abuild

will automatically use Visual C++. If you have cygwin installed

with gcc and the mingw runtime environment, abuild will attempt

to use gcc -mno-cygwin to build as long as you

set the MINGW environment variable to

1, though bear in mind that abuild's mingw

support is not entirely complete.

The directory cxx-library under

doc/example/basic contains a simple C++

library. Our library is called

basic-library. It implements the single C++

class called BasicLibrary using the header

file BasicLibrary.hh and the source file

BasicLibrary.cc. Here are the contents of

those files:

basic/cxx-library/BasicLibrary.hh

#ifndef __BASICLIBRARY_HH__

#define __BASICLIBRARY_HH__

class BasicLibrary

{

public:

BasicLibrary(int);

void hello();

private:

int n;

};

#endif // __BASICLIBRARY_HH__

basic/cxx-library/BasicLibrary.cc

#include "BasicLibrary.hh"

#include <iostream>

BasicLibrary::BasicLibrary(int n) :

n(n)

{

}

void

BasicLibrary::hello()

{

std::cout << "Hello. This is BasicLibrary(" << n << ")." << std::endl;

}

Building this library is quite straightforward. Abuild's build

files are generally declarative in nature: they describe what

needs to be done rather than how it is done. Building a C or C++

library is a simple matter of creating an

Abuild.mk file that describes what the names

of the library targets are and what each library's sources are,

and then tells abuild to build the targets using the C and C++

rules. Here is this library's Abuild.mk

file:

basic/cxx-library/Abuild.mk

TARGETS_lib := basic-library SRCS_lib_basic-library := BasicLibrary.cc RULES := ccxx

The string ccxx as the value of the

RULES variable indicates that this is C or C++

code (“c” or “cxx”). In order for

abuild to actually build this item, we also need to create an

Abuild.conf file for it. The existence of

this file is what makes this into a build item. We present the

file here:

basic/cxx-library/Abuild.conf

name: cxx-library platform-types: native

In this file, the name key is used to

specify the name of the build item and the

platform-types key is used to help abuild

figure out on which platforms it should attempt to build this

item. Finally, we want this build item to be able to make the

resulting library and header file available to other build items.

This is done in its Abuild.interface file:

basic/cxx-library/Abuild.interface

INCLUDES = . LIBDIRS = $(ABUILD_OUTPUT_DIR) LIBS = basic-library

This tells abuild to add the directory containing this file to

the include path, the output directory in which the generated

targets were created to the library path, and the

basic-library library to the list of

libraries to be linked with. Notice that the name of the library

assigned to the LIBS variable is the same as

the value assigned to the TARGETS_lib variable

in the Abuild.mk file, and that the

abuild-provided variable

$(ABUILD_OUTPUT_DIR) is used as the library

directory. All relative paths specified in the

Abuild.interface file are relative to the

directory that contains the Abuild.interface

file. They are automatically converted internally by abuild to

absolute paths, which helps to keep build items

location-independent.

To build this item, you would run the command

abuild in the

basic/cxx-library directory. Abuild will

create an output directory whose name would start with

abuild- and be based on the platform or

platforms on which abuild was building this item. This is the

directory to which the variable

$(ABUILD_OUTPUT_DIR) refers in the

Abuild.interface file.

There is a lot of capability hiding beneath the surface here and quite a bit of flexibility in the exact way in which this can be done, but this is the basic pattern you will observe for the majority of C and C++ library build items.

The directory basic/cxx-program contains a

simple C++ program. This program links against the library

created in our previous example. Here is the main body of our

program:

basic/cxx-program/program.cc

#include <BasicLibrary.hh>

int main()

{

BasicLibrary b(5);

b.hello();

return 0;

}

This program includes the BasicLibrary.hh

header file from the cxx-library build

item. Here is the Abuild.mk for this build

item:

basic/cxx-program/Abuild.mk

TARGETS_bin := cxx-program SRCS_bin_cxx-program := program.cc RULES := ccxx

Notice that this is very similar to the

Abuild.mk from the library build item. The

only real difference is that the TARGETS and

SRCS variables contain the word

bin instead of lib. This

tells abuild that these are executable targets rather than

library targets. Notice the conspicuous lack of any references to

the library build item or the location of the headers or libraries

that it makes available. A principal feature of abuild is that

this program build item does not need to know that information.

Instead, it merely declares a dependency on the

cxx-library build item by name. This is

done in its Abuild.conf:

basic/cxx-program/Abuild.conf

name: cxx-program platform-types: native deps: cxx-library

Notice the addition of the deps key in this

file. This tells abuild that our program build item

depends on the library build item. When

abuild sees this, it automatically makes all the information in

cxx-library's

Abuild.interface available to

cxx-program's build, alleviating the need

for the cxx-program build item to know the

locations of these files. This will also tell abuild that

cxx-library must be built before we can

build cxx-program.

To build this item, we just run the abuild

command as we did for cxx-library. This

will automatically build dependency

cxx-library before building

cxx-program. In this way, you can can

start a build from any build item and let abuild automatically

take care of building all of its dependencies in the correct

order.

The output of running abuild in the

cxx-program directory when starting from a

clean build is shown below. Your actual output will differ

slightly from this. In particular, the output below has the

string --topdir-- in place of the path to

doc/example, and the string

<native> in place of your native

platform.

[8]

Notice that abuild builds

cxx-library first and then

cxx-program:

basic-cxx-program.out

abuild: build starting abuild: cxx-library (abuild-<native>): all make: Entering directory `--topdir--/basic/cxx-library/abuild-<native>' Compiling ../BasicLibrary.cc as C++ Creating basic-library library make: Leaving directory `--topdir--/basic/cxx-library/abuild-<native>' abuild: cxx-program (abuild-<native>): all make: Entering directory `--topdir--/basic/cxx-program/abuild-<native>' Compiling ../program.cc as C++ Creating cxx-program executable make: Leaving directory `--topdir--/basic/cxx-program/abuild-<native>' abuild: build complete

To remove all of the files that abuild created in any build item's directory, you can run abuild clean in that directory. To clean everything in the build tree, run abuild --clean=all. More details of how to specify what to build and what to clean can be found in Chapter 9, Telling Abuild What to Build.

In our next example, we'll demonstrate how to build a simple Java

library. You will find the Java example in

basic/java-library. The files here are

analogous to those in our C++ library example. First, here is a

Java implementation of our BasicLibrary

class:

basic/java-library/src/java/com/example/basic/BasicLibrary.java

package com.example.basic;

public class BasicLibrary

{

private int n;

public BasicLibrary(int n)

{

this.n = n;

}

public void hello()

{

System.out.println("Hello. This is BasicLibrary(" + n + ").");

}

}

Next, look at Abuild.conf:

basic/java-library/Abuild.conf

name: java-library platform-types: java

This is essentially identical to our C++ library except that the

platform-types key has the value

java instead of the value

native. This is always true for Java build

items. Next, we'll look at the

Abuild.groovy file:

basic/java-library/Abuild.groovy

parameters {

java.jarName = 'java-library.jar'

abuild.rules = 'java'

}

Java build items have this file instead of

Abuild.mk. The contents are very similar.

The Abuild.groovy file contains Groovy code

that is executed inside a particular context provided by

abuild. Most Abuild.groovy files will

simply set parameters that describe what

will be built. In this file, we set the

java.jarName parameter to the name of the JAR

file we are creating, and we set the

abuild.rules parameter to the value

'java' to indicate that we are using the

java rules. For Java build items, we don't

explicitly list the source files. Instead abuild automatically

finds sources in a source directory which is, by default,

src/java. There are many more parameters

that can be set, and you have considerable flexibility about how

to arrange things and how to get files into your Java archives.

Abuild aims to allow you to build by

convention, but it gives you the flexibility to do

things your own way when you want to. We provide detailed

information about the directory structure for Java builds in

Section 19.3, “Directory Structure for Java Builds”.

Finally, look at the Abuild.interface file.

This file provides information to other build items about what

they should add to their classpaths in order to make use of the

JAR file created by this build item:

basic/java-library/Abuild.interface

declare java-library.archiveName string = java-library.jar declare java-library.archivePath filename = \ $(ABUILD_OUTPUT_DIR)/dist/$(java-library.archiveName) abuild.classpath = $(java-library.archivePath) abuild.classpath.manifest = $(java-library.archivePath)

You'll notice here that we are actually setting four different

variables. Not all of these are required, but the pattern here

is one that you may well wish to adopt, especially if you are

working in a Java Enterprise environment. The first statement in

the interface file declares a variable called

java-library.archiveName as a string and

initializes it to the value java-library.jar.

This syntax of declaring and initializing an interface variable

was introduced into abuild with version 1.1. Here we adopt a

convention of using the build item name as the first field of the

variable name, and the literal string

archiveName as the second field. By including

the name of the build item in the name of the interface variable,

we reduce the possibility of creating a name clash. By providing

a variable to hold the name of the archive provided by this build

item, we allow other build items to refer to this JAR file by

name without having to know what it is called. The second

interface variable, java-library.archivePath,

contains the full path to the archive. (Notice that abuild

puts the JAR file in the dist subdirectory

of the abuild output directory.) This enables other build

items to refer to this archive by path without knowing any

details beyond this naming convention and the name of the

providing build item. Making this type of information available

in this way is not necessarily a straight Java “SE”

environment, but it can be very useful in a Java “EE”

environment where build items that create EAR files may have to

reach into other build items to package their artifacts in higher

level archives. Experience has shown that adopting a convention

like this and following it consistently will pay dividends in the

end.

After setting these two build-item-specific variables, we assign

to two built-in variables: abuild.classpath,

and abuild.classpath.manifest. Most simple

JAR-providing build items will do this. Abuild actually

provides multiple classpath variables, each of which is intended

to be used in a particular way. For a discussion, please see

Section 17.5.3, “Interface Variables for Java Items”.

As with the C++ library, it is possible to build this item by

running abuild from the

basic/java-library directory.

In Java, there is no deep distinction between a

“library” and a “program” except that a

JAR file that provides a program must have a

main method. If a JAR file contains a main

method, it can be executed, though it can also be used as a

library. Here are the relevant files for the program example:

basic/java-program/src/java/com/example/basic/BasicProgram.java

package com.example.basic;

import com.example.basic.BasicLibrary;

public class BasicProgram

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

BasicLibrary l = new BasicLibrary(10);

l.hello();

}

};

basic/java-program/Abuild.conf

name: java-program platform-types: java deps: java-library

basic/java-program/Abuild.groovy

parameters {

java.jarName = 'java-program.jar'

java.mainClass = 'com.example.basic.BasicProgram'

java.wrapperName = 'java-program'

abuild.rules = 'java'

}

A JAR file's manifest file may identify a class that contains a

main method. Abuild adds the

Main-Class attribute to the manifest file

when the java.mainClass parameter is set in

the Abuild.groovy. In addition, abuild

will create a wrapper script if the

java.wrapperName parameter is set. The

wrapper script that abuild creates may be useful for casual

execution of the Java program for testing purposes, but it is

generally not a substitution for having your own deployment

mechanism. In particular, the wrapper script references items

from your classpath by their paths within the build structure,

and additionally, abuild's wrapper scripts are not as portable

as the Java code that they help to invoke.

[9]

Here is the output of running abuild in this

directory. As in the C++ program example, the output has been

modified slightly: in addition to the

--topdir-- substitution, we have also filtered

out time stamps and other strings that could potentially differ

between platforms:

basic-java-program.out

abuild: build starting

abuild: java-library (abuild-java): all

[mkdir] Created dir: --topdir--/basic/java-library/abuild-java/classes

[javac] Compiling 1 source file to --topdir--/basic/java-library/abu\

\ild-java/classes

[mkdir] Created dir: --topdir--/basic/java-library/abuild-java/dist

[jar] Building jar: --topdir--/basic/java-library/abuild-java/dist\

\/java-library.jar

abuild: java-program (abuild-java): all

[mkdir] Created dir: --topdir--/basic/java-program/abuild-java/classes

[javac] Compiling 1 source file to --topdir--/basic/java-program/abu\

\ild-java/classes

[mkdir] Created dir: --topdir--/basic/java-program/abuild-java/dist

[jar] Building jar: --topdir--/basic/java-program/abuild-java/dist\

\/java-program.jar

abuild: build complete

[8] All example output in this document is normalized this way since it all comes directly from abuild's test suite. Testing all the examples in the test suite guarantees the accuracy of the examples and ensures that they work as advertised on all platforms for which abuild is released. Should you wish to study abuild's test suite with the examples, be aware that the bold italicized text preceding each block of example output is the name of the expected output file from the test suite.

[9] Specifically, abuild generates different wrapper scripts depending on whether you're running on Windows or not. Although it would work to build Java code on UNIX and run it on Windows, or vice versa, wrapper scripts generated on one platform are not portable to the other.

In this part of the manual, we discuss the standard features of abuild. For most ordinary build problems, these chapters provide all the information you will need. A few advanced topics are presented here. Where appropriate, they include cross references to later parts of the document where functionality is covered in more depth. By the end of this part, you should have a reasonably complete understanding of the structure of abuild's build trees, and a fairly complete picture of abuild's overall functionality. You will know enough about abuild to be able to use it for tasks of moderate complexity.

Table of Contents

- 4. Build Items and Build Trees

- 5. Target Types, Platform Types, and Platforms

- 6. Build Item Dependencies

- 7. Multiple Build Trees

- 8. Help System

- 9. Telling Abuild What to Build

- 10. Integration with Automated Test Frameworks

- 11. Backing Areas

- 12. Explicit Read-Only and Read/Write Paths

- 13. Command-Line Reference

- 14. Survey of Additional Capabilities

Table of Contents

Now that we've had a chance to see abuild in action for a simple case, it's time to go into more detail about how things fit together. In Section 3.2, “Basic Terminology”, we briefly defined the terms build item, build tree, and build forest. In this chapter, we will describe them in bit more detail and briefly introduce a number of concepts that apply to them.

A precise definition of build item would

state that a build item is any directory that contains an

Abuild.conf. Perhaps a more useful

definition would say that a build item is the basic object that

participates in abuild's object-oriented view of a software

build. A build item provides some service

within a build tree. Most build items build some kind of code:

most often a library, executable, or Java archive. Build items

may provide other kinds of services as well. For example, a

build item may implement a code generator, support for a new

compiler, or the ability to make use of a third-party software

library. In addition, a build item may have certain attributes

including a list of dependencies, a list

of supported flags, information about what

types of platforms the build item may be built on, a list of

traits, and other non-dependency

relationships to other build items. Each of these concepts is

explored in more depth later in the document.

All build items that provide a service are required to have a name. Build item names must be unique within their build tree and all other build trees accessible to their build tree since the build item name is how abuild addresses a build item. Build item names consist of period-separated segments. Each segment may contain mixed case alphanumeric characters, underscores, and dashes. Build item names are case-sensitive.

The primary mechanism for describing build items is the

Abuild.conf file. This file consists of

colon-separated key/value pairs. A complete description of the

Abuild.conf file may be found in Chapter 15, The Abuild.conf File. In the mean time, we will

introduce keys as they become relevant to our discussion.

Although every build item has an Abuild.conf

file, there are various other files that a build item may have.

We defer a complete list and detailed discussion these files for

later in the document, but we touch briefly upon a few of the

common ones here.

Abuild.confThis is the most basic of the build item files, and it is the only file that must be present for every build item. We sometimes refer to this as the build item configuration file.

Abuild.mk,Abuild.groovyThese are the files that direct abuild what to actually build in a given build item. Each build file is associated with a specific backend. Exactly one of these files must be present in order for abuild to attempt to build a build item. As such, these files are known as build files. When we say that a build item has or does not have a build file, we are specifically talking about one of these files. In particular, it is important to note that

Abuild.confandAbuild.interfaceare not considered build files. [10]Abuild.interfaceThe

Abuild.interfacefile is present for every build item that wants to make some product of its build accessible to other build items. We refer to this as the build item's interface file. There has been some confusion among some abuild users about the term interface. Please understand that abuild interfaces are distinct from Java interfaces, C++ header files, and so forth, though they serve essentially the same function. If you view a build item as an object, the abuild interface contains information about what services that object provides. It exposes the interfaces through which other build items will access a given build item's products.

A build tree, as defined before, is a collection of build items

arranged hierarchically in the file system. Like build items,

build trees have names, and are only referred to from other build

trees by name. The root of a build tree is a build item whose

Abuild.conf contains the

tree-name key. We refer to this item as the

tree's root build item.

A build tree is formed as a result of the items it contains

holding references to the locations of their children within the

file system hierarchy. These locations are named as relative

paths in the child-dirs keys of the items'

Abuild.conf files. It is customary to have

the value of child-dirs contain single path

elements (i.e.just a directory without any

subdirectories), but this is also not a requirement:

child-dirs entries may contain multiple path

elements as long as there are no Abuild.conf

files in any of the intermediate directories. If a build item's

child contains its own tree-name key, that

child build item is the root of a separate build tree that is

part of the same forest, defined below. Otherwise, the child

build item is part of the same tree as its parent.

In addition to containing build items, build trees can contain

other attributes. Among these are references to other build

trees, a list of supported traits, and a

list of plugins. We will discuss these

topics later in the document. These attributes are defined using

keys in the root build item's Abuild.conf

file.

A build forest is a collection of build trees that are connected

to each other by virtue of one tree's root build item being

referenced as a child of a build item in another tree in the

forest. When abuild starts up, it looks for an

Abuild.conf in the current directory. It

then walks up the file system one directory at a time looking for

additional Abuild.conf files. Eventually,

it will either find the topmost Abuild.conf

file, or it will find an Abuild.conf file

that is not listed as a child of the next higher one. Whichever

of these cases is found first, the resulting

Abuild.conf file is the root of the build

forest. The forest then consists of all the trees encountered by

following all the child-dirs pointers from

the forest root.

Note that, unlike with build items and trees, forests do not have names. Note also that, unlike with trees, there is no explicit marker of the root of a build forest. This is very important as it allows you to extend a forest from above without modifying the forest itself. For a more in-depth discussion, see Chapter 7, Multiple Build Trees.

Note that the hierarchy defined by the layout of build items in the file system is a file system hierarchy and nothing more. It doesn't have to have any bearing at all on the dependency relationships among the build items. That said, it is sensible to organize build items in a manner that relates to the architecture of the system, and this in turn usually has implications about dependencies. Still, it is important to keep in mind that abuild is not file-system driven but rather is dependency driven.

In further describing build items and their attributes, it is useful to classify build items into several types. Most build items serve the purpose of providing code to be compiled. There are a number of special types of build items that serve other purposes. We discuss these here:

- root

The root build item of a build tree is the topmost item in that tree. It has a tree-name key that gives the name of the build tree. It is often the case that the root build item serves no purpose other than to hold onto tree-wide attributes. It is therefore permissible for a root build item to lack a name key. (See below for a discussion of unnamed build items.) Keys that define attributes of the build tree may appear only in the root build item's

Abuild.conf.- unnamed

In order to refer to one build item from another, both build items must have names. Abuild requires that every named build item in a build forest be named uniquely within that forest. A name is given to a build item by setting the name key in its

Abuild.conf. Sometimes, a build item exists for the sole purpose of bridging its parent with its children in the file system. Such items do not need to be referenced by other build items, so they do not need names. The only use of an unnamed build item is to serve as an intermediary during traversal of the file system. Such a build item'sAbuild.confmay only contain the child-dirs key. Abuild doesn't retain any information about these build items. It simply traverses through them when locating build items at startup time. Unnamed build items are the only types of build items that don't have to belong to any particular build tree. It is common for the root of a forest to be an unnamed build item whose children are all roots of build trees.- interface-only

Interface-only build items are build items that contain (in addition to

Abuild.conf) anAbuild.interfacefile. They do not build anything and therefore do not contain build files (such asAbuild.mkorAbuild.groovy). Since they have nothing to build, abuild never actually invokes a backend on them. They are, however, included in all dependency and integrity checks. A typical use of interface-only build items would be to add the locations of external libraries to the include and library paths (or to the classpaths for Java items). There may also be some interface-only build items that consist solely of static files (templated C++ classes, lists of constants, etc.). Interface-only build items may also be used to declare interface variables that are used by other build items.- pass-through

Pass-through build items are useful for solving certain advanced abuild problems. As such, there are aspects of this definition that may not be clear on the first reading. Pass-through build items contain no build or interface files, but they are named and have dependencies. This makes pass-through build items useful as top-level facades for hiding more complicated build item structures. This could include build items that have private names relative to the pass-through item, and it could also include structures containing build items that cross language and platform boundaries. Several examples in the documentation use pass-through build items to hide private build item names. For further discussion of using pass-through build items in a cross-platform environment, please see Section 24.4, “Dependencies and Pass-through Build Items”.

- plugin

Plugins are capable of extending the functionality of abuild beyond what can be accomplished in regular build items. Plugins must be named and not have any dependencies. No other build items may depend on them. Plugins are a topic in their own right. They are discussed in depth in Chapter 29, Enhancing Abuild with Plugins.

Virtually every software development project has some need to

integrate with third-party software libraries. In a traditional

build system, you might list the include paths, libraries, and

library directories right in your Makefile,

build.xml, or configuration file for

whatever build system you are using. With abuild, the best way

to integrate with a third-party library is to use a build item

whose sole purpose is to export that library's information using

an Abuild.interface file. In the simplest

cases, a third-party library build item might be an interface

only build item (described above) that just includes the

appropriate library directives in a static

Abuild.interface file. For example, a build

item that provides access to the PCRE (Perl-compatible regular

expression) libraries on a Linux distribution that has them

installed in the system's standard include path might just

include an Abuild.interface with the

following contents:

LIBS = pcrecpp pcre

For Java build items, a third-party JAR build item would

typically append the path to the JAR file to the

abuild.classpath.external interface variable.

(For a discussion of the various classpath variables, see Section 17.5.3, “Interface Variables for Java Items”.)

Sometimes, the process may be more involved. For example, on a

UNIX system, it is often desirable to use

autoconf to determine what interface

is required for a particular library. We present an example of

using autoconf with abuild in Section 18.3, “Autoconf Example”. Still other libraries may use

pkg-config. For those libraries, it

may make sense to create a simple set of build rules that

automatically generate an Abuild.interface

after-build file (also discussed in Section 18.3, “Autoconf Example”) by running the

pkg-config command. An example

pkg-config build item may be found in

the abuild-contrib package available at

abuild's web site.

Whichever way you do it for a given package, the idea is that you should always create a build item whose job it is to provide the glue between abuild and the third-party library. Other build items that need to use the third-party library can then just declare a dependency on the build item that provides the third-party library's interface. This simplifies the process of using third-party libraries and makes it possible to create a uniform standard for doing so within any specific abuild build tree. It also alleviates the need to duplicate information about the third-party library throughout your source tree. Whenever you are duplicating knowledge about the path of some entity, you would probably be better off creating a separate build item to encapsulate that knowledge.

[10]

Additionally, the files

Abuild-ant.properties and

Abuild-ant.xml are recognized as build

files, associated with the deprecated xml-based ant backend.

Abuild was designed with multiplatform operation in mind from the beginning. Up to this point, we have largely glossed over how abuild deals with multiple platforms. In this chapter, we will cover this aspect of abuild's operation in detail.

Abuild classifies platforms into a three-level hierarchy. The three levels are described by the following terms:

- target type

A target type encompasses the overall kind of targets that are being built. A target type essentially encapsulates a build paradigm. Abuild understands three target types: platform-independent for truly platform-independent products like scripts and documentation, object-code for compiled object code like C and C++, and java for Java byte code and related products. One could argue that Java code is platform-independent, but since Java code has its own build paradigm, abuild considers it to be a separate target type. Be careful not to confuse target type with target, defined in Section 3.2, “Basic Terminology”.

- platform type

A platform type essentially defines a grouping of platforms. Platform types belong to target types and contain platforms. When configuring build items, developers assign build items to platform types rather than to platforms or target types. The platform-independent target type has only platform type: indep. The java target type has only one platform type: java. [11] Platform types are most useful in the object-code target type. Abuild has only one built-in platform type in the object-code target type: native. The native platform type applies to build items that are expected to be able to be built and run on the host platform. Additional platform types to support embedded platforms or cross compilers can be added in plugins (see Section 29.3, “Adding Platform Types and Platforms”).

- platform

The abuild platform is the lowest level of detail in describing the environment in which a target is intended to be used. The expectation is that compiled products (object files, libraries, binary executables, java class files, etc.) produced for one platform are always compatible with other products produced for that platform but are not necessarily compatible with products produced for a different platform. If two different versions of a compiler generate incompatible object code (because of incompatible runtime library versions or different C++ name mangling conventions, for example), then a host running one compiler may generate output belonging to a different platform from the same host running a different version of the compiler. For the indep platform type in the platform-independent target type, there is only one platform, which has the same name as the platform type: indep. For the java platform type in the java target type, there is also only one platform, which also shares its name with the platform type: java. Platforms become interesting within the object-code target type. When we refer to platforms, we are almost always talking about object-code platforms.

This table (Table 5.1, “Built-in Platforms, Platform Types, and Target Types”) shows the target types along with the built-in platform types and platforms that belong to them.

Table 5.1. Built-in Platforms, Platform Types, and Target Types

| Target Type | Platform Type | Platform |

|---|---|---|

| object-code | native | based on available tools |

| java | java | java |

| platform-independent | indep | indep |